The Terminator was one of those meteoric, Hollywood fairy tales that seem wonderfully far-fetched under the current, studio-mandated production model. Here was James Cameron, a young Canadian special effects artist (self taught, no less) with two films under his directorial belt: Xenogenesis, a science-fiction short with obvious thematic and aesthetic roots in Star Wars; and Piranha II: The Spawning, a shlock budget horror film, borne from the B-movie genesis tank of Roger Corman. Neither release was particularly notable, aside from demonstrating Cameron’s tenacity and willingness to learn and create.

From those humble origins sprang a film about a malicious, time-travelling cyborg assassin, that, on paper, seemed every bit as ridiculous as the progenitors that paraded luridly from Corman’s eclectic banner. A box office return of $78 million from a meagre budget of $6.4 million for Cameron’s stark, noir-ish visual and psychological onslaught established his well-earned reputation as an auteur. It was further cemented in Aliens and The Abyss, but it wasn’t until 1991’s Terminator 2: Judgement Day (hereon T2) that Cameron truly brandished his abilities as a director.

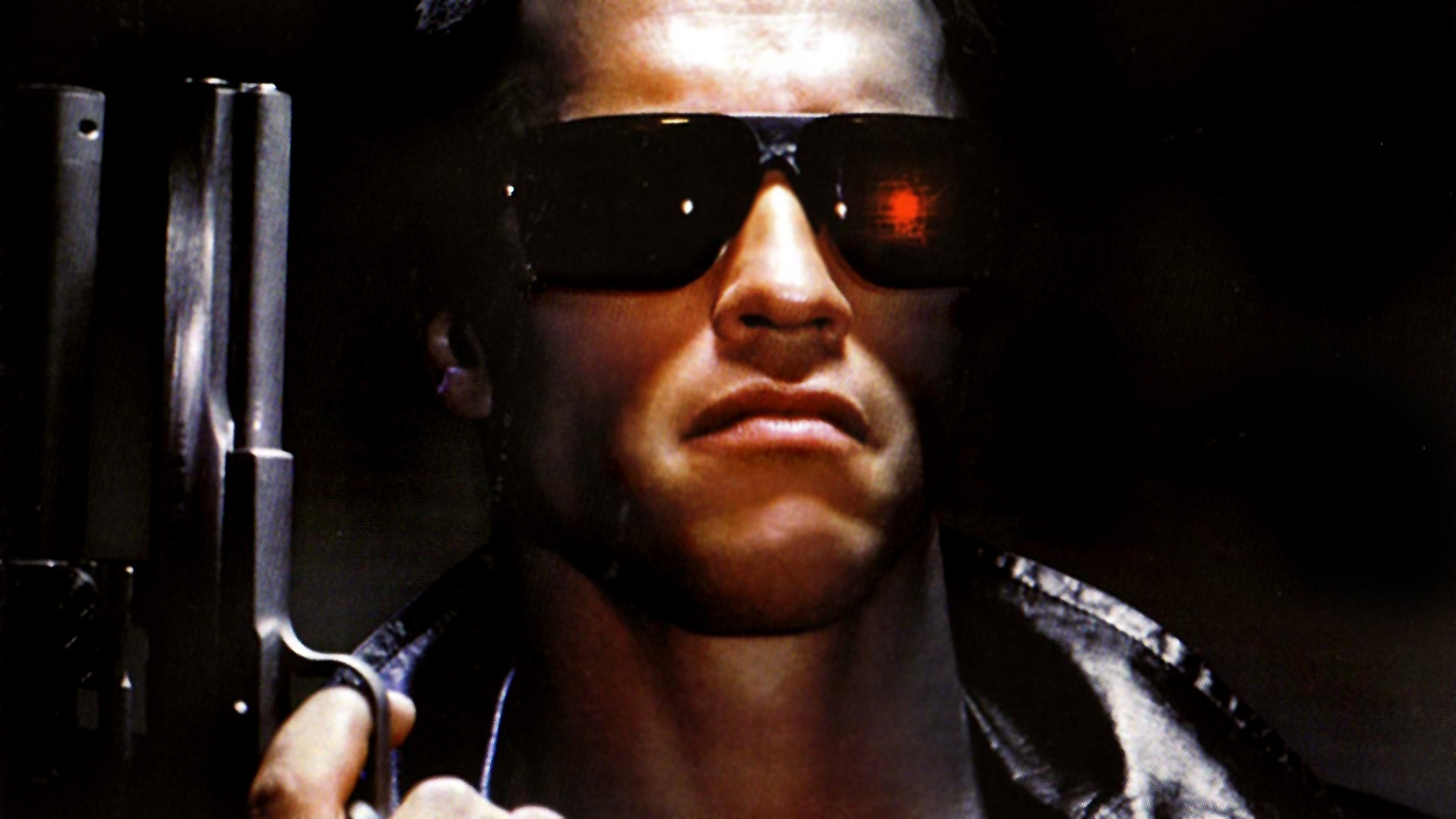

While The Terminator crafted a truly terrifying character in the Terminator itself, it did little with the human characters. They were merely ancillary objects to further alienate the Terminator from the world that it had arrived at, and to great effect. The Terminator is truly Schwarzenegger’s film, even with the scant, monosyllabic 18 lines of script he was graced with. As an audience, we care less about the overall plight of Kyle and Sarah and more about their real-time interactions with the Terminator.

T2, however, embraces the concept of humanity, which allows the audience to engage with its characters beyond the primal question of ‘will they/won’t they survive?’. It’s portrayed not only in the greatly juxtaposed depictions of the two Terminators, but in the emotionally resonant figures of John and Sarah.

The intent of the Terminators conveyed almost immediately. Schwarzenegger’s T-800 model Terminator is depicted as physically imposing, but cautious. It carefully scans the environment it arrives in, and only engages in combat after provocation. Cameron’s choice of a biker bar and the immediate hostility displayed as the T-800 enters gives the audience a reason to back the Terminator in the ensuing scuffle. Cameron gives Schwarzenegger the first of many superb catch phrases (“I need your clothes, your boots, and your motorcycle”) before lightening the violent tone of the scene with George Thorogood and the Destroyers’ song, Bad to the Bone. The entire scene confirms the T-800’s status as an American, as bizarre as that sounds: not only does it overcome the threats from a hostile group of bullies, it rides off into the night on a motorbike (wearing sunglasses, no less) to become the epitome of the modern cowboy with a classic American song as backing. It’s all vaguely ridiculous, but charmingly so – it is somewhat difficult to dislike the T-800, despite it’s violent tendencies.

The T-800’s introduction is immediately contrasted with the T-1000’s. This is ominous, cold and calculated – done quickly, brutally, without words, and backed by a mechanical, percussive musical score. There is no hesitation in the T-1000’s slaughter, and the choice of an innocent, law-enforcement figure as its first victim directly enforces an ‘anti-American’ character. The T-1000’s continued impersonation as a police officer throughout provides two possible trains of thought for an American audience: the inherent abuse of a trusted figure of American culture and the anger it inspires; or the subtle proliferation of the trope that “cops can’t be trusted”. Neither viewpoint is positive: if it is difficult to dislike the T-800, it is equally difficult to like the T-1000.

Further reasons to like the trio of John, Sarah and the T-800 are presented almost immediately afterward. Sarah’s incarceration as a “schizo” for reasons that the audience already knows to be false (the existence of the Terminators, thanks to the opening scenes) is given more impetus for outrage as a result of the truly reprehensible staff of the facility she is imprisoned in. They peer in through the tiny window of her cage and view her not as someone to be pitied, but as animalistic and psychotic – a vessel for the delivery of physical and psychological abuse under the auspice of mental care. It makes the T-800’s rescue of Sarah all the more satisfying, as the ‘all-American hero’ dispatches its somewhat morally-acceptable vengeance upon the guilty.

It’s important to note the T-800’s characterisation as a ‘gentle giant’ – seemingly indestructible, but simplistic in its understanding of the world. Similar tones are demonstrated in Brad Bird’s sublime, 1999 animated film, The Iron Giant, as the titular character lives simply, but compassionately under its limited understanding of the rules of the world. Both characters feature physical attributes that betray their mechanical underpinnings, but they express an earnestness and humanity that the audience can easily connect with. They sit in the same section of the uncanny valley that characters such as C3P0 and R2-D2 do: that of clearly unrealistic, physical portrayals of humanoid figures that the audience can happily empathise with as a result of their human-like observations and actions.

This human touch is the key between John’s relationship with the T-800. Their pairing forms a kind of dual father figure dichotomy – John initially has to teach the T-800 the value of morals, with the T-800 obeying his commands as a child would, while the T-800 finally gives John a hero to look up to – something that his upbringing has consistently lacked. Just as Luke Skywalker does in Star Wars, John gives the audience their entry point to the world. John is aware of Sarah’s history, but he is not clued in to its significance, nor is even fully aware of the complete details of it. This is essentially the same situation the audience is in, affording them the ability to see themselves in John. His immense likability (the rebellious cheekiness counteracted with his love and passion) ensure that the audience consistently barracks for John, even as they occasionally question the motives and actions of Sarah and the T-800.

The trio balance each other’s primary motivators while they seek the same goal. Sarah’s are blinding fury, driven by terror; John’s are determination and optimism, driven by love; and the T-800’s are resolve and power, driven by adherence to the rules of its world. This creates a harmonious and thematically pleasing grouping as the different viewpoints bounce and interact off each other. All viewpoints are directly witnessed by the audience as well: they are not passively implied, but directly shown. Sarah’s flashbacks and premonitions create a consuming sense of dread, while John’s interactions with Sarah and the T-800 give a touch of warmth in an otherwise bleak world. The audience is not told that these characters feel this way: it is shown.

To date, Cameron has yet to inject this kind of wonderfully subtle (and exquisitely effective) thread of emotional resonance into any of his other titles. It is, of course, this writer’s opinion, but Titanic erred on the side of pantomime in its portrayal of the villain, and headlong into the realm of abject fantasy for the romance story, whereas Avatar and its heavy-handed attempts at making the audience care for its array of thinly-written characters felt like a sledgehammer being used for delicate neurosurgery.

And yet, like those two examples, T2 is an action film. A bona-fide, high-budget, high octane, action film. Every cent of its $100 million budget was spent in ensuring the film bled action with every frame. This is precisely why T2 is so good: when the action dies down, there’s still an equally watchable collection of characters to love, hate and care for. That goes without needing to mention the action itself, which is thrilling and wonderfully engaging – a perfect confluence of elements. It exists in the rather sparse world of sequels that greatly surpass the quality of their forebears to become something more than a good film in their respective franchise. They become iconic and impervious to the fortunes of the films that follow them. It does not matter that the Terminator franchise currently lies in a ruinous wreck. T2 does not need the franchise: it is the franchise.

Comments